Nicholas L. Johnson

My online academic portfolio

Ritualized Drama’s Representation of Ma’at Preserved Egyptian Social Order

Egyptian society constructed its social order on the foundations of the political and mythological concept of Ma’at. The representation of Ma’at pervades the Egyptian dramatic rituals and was the ideal that defined the social hierarchy, ultimately legitimizing the pharaoh. It was the repetitive rituals invoking Ma’at that legitimized the pharaoh but also held him or her accountable for both natural and social occurrences. This repetition also allowed political leaders to assess and reassess the prosperity of Egyptian society. The stability of Egyptian society depended on the repetitive representation of Ma’at in dramatized rituals as a means of encouraging reevaluation of the Egyptian state.

Ma’at had two conceptualizations in Egyptian society which demonstrates its prominent influence over the Egyptian mode of thinking. It represented the cosmological balance and the divine order established over all of creation (Hornung 1992: 134). Ma’at also justified the kingship and the social hierarchy that persisted in Egypt. Egyptians depicted it as the conflict of a contemporary king overcoming the rift in order that accompanied the death of his or her predecessor to unite with the natural, divine order of Ma’at. In this sense, the societal role of Ma’at encompassed and complemented its cosmological role, because the pharaoh was seen as the “sole intermediary for his subjects” with the gods, who upheld the cosmological side of Ma’at (Bard 2015: 138; Kernodle 1989: 21). As both the divine and societal order, Egyptian society idealized living in accordance to the values of Ma’at.

As a justification of the Egyptian social hierarchy, the concept of Ma’at refers to several societal values that imply a desire to constantly review the Egyptian state. First, those of higher status in the social hierarchy had a greater responsibility to act in accordance to Ma’at. The more power one had in the Egyptian order, the more responsibility one had to uphold Ma’at, and this gave most of the responsibility to the pharaoh at the top of the social hierarchy, who oversaw the preservation of the divine order made earthly (Hornung 1992: 141). Upon this responsibility, the elites acted to exemplify Ma’at in one’s daily life so as to disseminate its validity as a social ideal. Exemplifying Ma’at had to be constantly reevaluated, as the representation of Ma’at changed incrementally with the reestablishment of order with each new pharaoh, and so Egyptian society must have contemplated and consciously striven for how to embody Ma’at as society’s needs changed (Gillam: 151; Hornung 1992: 135). Thus, Egyptian society also valued flexible systems to uphold the political order. While Ma’at itself was “the norm that should govern all actions, the standard by which all deeds should be measured or judged”, it could not become a stagnant order because then the stable, gradual manner of Egyptian societal change would lead to political rancor (Hornung 1992:136). Egyptians wanted to avoid this political rancor so as to maintain the same socio-political hierarchy instead of creating a new one.

A desire to maintain the pre-existing social order over establishing a new social order recurs in the social values inherent in Ma’at. The prevalence of reaffirming the established Egyptian order and the absence of creating a new order in Egyptian records suggests that the Egyptian society intended to maintain and adapt its already established order to the necessities of the slowly changing political climate (Baines 2006: 292). Being the prevailing order concept across the periods of Egyptian autonomy, Ma’at relied on the social values of flexibility, exemplification, and responsibility to survive and revive after each of the Intermediate Periods to centralize power once again under the pharaoh. The dramatized rituals of Egypt enhance these social values by employing them as themes, and so made these rituals indispensable to the order of Egyptian society.

Baines recognizes “the centrality of ritual and performance, including performance as public display, in constituting, representing, and sustaining authority in and between societies” (Baines 2006: 261). Performance as a tool or instrument of expression therefore provides more than entertainment to a society. In Egyptian society, the performance of ritualized dramas acts as a manifestation, representation, and promoter of Ma’at, which protects the social hierarchy and the power of the pharaoh.

One such ritualized drama, The Triumph of Horus, focuses thematically on Ma’at and pharaonic responsibility. The text, as translated, by H. W. Fairman, contains themes connected to the pharaoh and the perpetuation of one, adaptable order. The main character performing actions is Horus, who in Egyptian society is strongly associated with the living pharaoh (Fairman 1974; Kernodle 1989: 21). As such, Horus’ taking action in the hunt of the hippopotamus, a representation of Seth, and chaos by extension, emphasizes the pharaoh’s responsibility at the top of the hierarchy to exemplify and to uphold Ma’at (Mitchley and Spalding 1982: 26). The chorus calls out to Horus repeatedly during his struggle with the hippopotamus, “Hold fast, Horus, hold fast!” (Fairman 1974). This encouragement has a two-fold purpose in the perspective of upholding Ma’at. The chorus represents the Egyptian people, who implore their pharaoh to act on his responsibility and embody the forces of the cosmological order to dispel the forces of chaos, or isfet. To maintain the Egyptian social order, while ensuring that it suitably functions and adapts to the current needs of society, is represented in Horus’ many attacks on the Hippopotamus. Horus injures the hippopotamus many times to vanquish the representation of chaos, showing his own versatile persistence. Thus, The Triumph of Horus conveys the societal values of flexibility, exemplification, and responsibility in its ritualized, dramatic form. As one of the completely translated dramatic texts of Egypt, The Triumph of Horus is a large window into the Egyptian culture of ritualized drama, but it does not stand alone.

The metaphor of Horus to represent the pharaoh repeats itself in many of the rituals of Egypt because it drew upon the cosmological understanding of order to ensure that order would be maintained in human society as well. Other rites such as the Confirmation of Royal Power in the New Year and the Enthronement of the Sacred Falcon invoked Horus as a symbol for protection and reciprocity (Gillam 2005). Horus also overcomes Seth, who slayed Horus’ father and the preceding king, Osiris, to reestablish the divine sense of Ma’at. This is a metaphor for the pharaoh who takes the place of the preceding king, as the loss of the pharaoh destroys the sense of order that the Egyptian society had established under that particular king and now the order must be established yet again under the new pharaoh (Kernodle 1989: 21).

Another ritualized drama, the Egyptian Ramesseum Drama, contains many symbols of Ma’at. This ritualized drama took place on a barque and traveled to as many temples as possible in a procession throughout Egypt (Gaster 1961: 375). From a logistical standpoint, this promoted Ma’at in that it did not require elites to travel to hear the societal doctrine of Ma’at. This allowed the Egyptian hierarchy to remain in its place and maintain order as it learned what was necessary to uphold this order.

The actual plot of the ritualized drama focuses on the coronation of Horus. Set, yet again the mythological representation of chaos, must hold the body of the previous king, Osiris, as Horus is given the Eye of Power and makes sacrifices of a goat and a goose, two representations of Set, whose heads are then flung beside a djed pillar,

which represents divine order and peace as seen at Djoser’s Step Pyramid (Figures 1 and 2). The djed pillar is then raised in the hands of Horus’ attendants and placed on Set’s back (Gaster 1961: 386). This imagery of Ma’at conquering the chaos that attempts to destroy it in the Egyptian Ramesseum Drama connects to the exemplification and responsibility values requisite to uphold Ma’at. The attendants’ putting the djed pillar on Set’s back represents the responsibility of the Egyptian people to exemplify Ma’at in their daily lives. Ma’at pervaded the Egyptian rituals because it was the best way to start the dissemination of societal values that Egypt used to maintain its order.

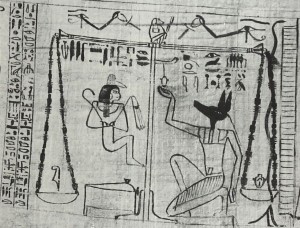

The ritualized dramas may have been sparsely attended, and solely by the elites. Any inscriptions of the rituals were also inaccessible to the Egyptian peasantry due to the dominant proportion of society that was illiterate (Baines 2006: 266). The elites, who benefitted from these performances, then reciprocated on their responsibility to maintain Ma’at in Egyptian society in symbols that the peasantry could actually access through the construction of large monuments. This suggests that upholding Ma’at was everyone’s responsibility, and depictions indicate that the conditions of one’s Afterlife depended on weighing their hearts against the Feather of Ma’at, a common symbol of the deity that embodied the divine, cosmic order (Figure 3).

For large spaces, the chambers within pyramid complexes could not accommodate large crowds of spectators, which leads to the speculation that these ritualized dramas were not intended to have audiences (Baines 2006: 262; Sauneron as qtd. In Lichtheim 1977: 122). The absence of an audience may directly contradict the concept that Ma’at was everyone’s responsibility. The purpose of mythological rituals however was not to be seen but to be understood: the conveyor of “human concepts into the abstract form of myth” (Kernodle 1989: 22). The Egyptian society may have converted their metaphorical myths into performances to inspire the construction of elaborate, yet orderly monuments that also symbolize the order they were trying to preserve. The social elite represented Ma’at for the peasantry in the form of grandiose temples, palaces, burial tombs, and other monumental architecture. Egyptian monumental architecture was celebrated during and after construction, which implies that Egyptian society from all levels of the hierarchy were involved in the process of building these symbols of Ma’at (Baines 2006: 262, 292-3). These monuments were the manifestation of the hierarchical responsibility to exemplify and uphold the concept of Ma’at which the elites and royals understood through their attendance and participation in rituals and dramas. The ritualized dramas of Egyptian society stabilized the social hierarchy by instilling the responsibility in elites to exemplify and disseminate the idea of Ma’at to the peasantry.

Representation of Ma’at in ritualized drama was a tool for evaluation of the state while also maintaining its power dynamic. Consistently performing these rituals over and over again provided the opportunity for this stable social hierarchy to evaluate its validity and prosperity. The repetitive tradition of the ritualized dramas empowered the stable hierarchy to reform as needed, through constant reflection on the state of Egyptian society (Kernodle 1989: 21). A necessity to actively analyze the order of the Egyptian world at all times even appears in the conceptualization of the peasant duty in regards to Ma’at, and so ritualized drama of Egypt inspired the symbolic structures that allowed the Egyptian peasantry to also participate in the socio-political order of their society (Hornung 1992: 135).

The prevalence of Ma’at in Egyptian society is due to its diversely useful nature as a social construct. It permitted the system in which it operated to perpetuate and reform itself. Ma’at appears in several central rituals, such as the ritualized drama, The Triumph of Horus, which conveyed to the elites that all Egyptians were responsible for living in accordance with Ma’at and for helping to uphold and disseminate its message through whatever reforms arose. The ideological tenet weathered several periods of societal dissolution and reformation, because it did not attempt to eradicate chaos, but merely to reestablish itself as the social order after it was lost whether as temporarily as after the death of a pharaoh or as long-lasting as any of the Intermediate Periods. Ma’at was a self-preserving aspect of Egyptian society, because it combined the deference for the traditions, in the responsibility to exemplify the social order with an acknowledgement that a lasting society required the flexibility to adapt, even in as predictable an environment as the banks and delta of the Nile. Performance of ritualized dramas emphasized maintenance and reflection to stabilize the Egyptian social order over several dynasties and periods of social unrest. The Egyptian society would not have lasted as long had Ma’at not been a central theme underlying its ritualized dramas.

Bibliography

Baines, John

2006 Public Ceremonial Performance in Ancient Egypt: Exclusion and Integration. In Archaeology of Performance: Theaters of Power, Community, and Politics. Edited by Takeshi Inomata and Lawrence S. Coben, p. 261–302. Archaeology in Society Series, Vol. 2, AltaMira Press, Lanham, Maryland.

Fairman, H.W.

1974 The Triumph of Horus. University of California Press, Los Angeles.

Gaster, Theodor Herzl

1961 Thespis; ritual, myth, and drama in the Ancient Near East. Harper & Row, New York.

Gillam, Robyn

2005 Performance and Drama in Ancient Egypt. Gerald Duckworth, London.

Hill, J.

“Ancient Egyptian Monuments: Djosers Step Pyramid.” Ancient Egypt Online. 2010. Electronic image, http://www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/djosersteppyramid2.html, accessed 24 Feb. 2016.

Hornung, Erik

1992 Idea into Image: Essays on Ancient Egyptian Thought. Translated by Elizabeth Bedeck. Timken Publishers, New York.

Kernodle, George R.

1989 The Theatre in History. The University of Arkansas Press, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Lichtheim, Miriam.

1977 “Reviewed Work: The Triumph of Horus, An Ancient Egyptian Sacred Drama by H. W. Fairman.” Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 69: 121–122. Electronic document, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23868107?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents, accessed January 31, 2016.

Tinkler, Michael.

2013 “Djed Pillars Used as a Frieze, Funerary Complex of Zoser, Saqqara.” Electronic image, https://www.flickr.com/photos/michaeltinkler/8585811066/in/photostream/, accessed 24 Feb. 2016.